After the death of his first wife (Sherifa) in February 1959, Wolff reports that he experienced four psychical effects: First was the arousal of a death wish; the second effect was a “forced passing through an enantiodromia”—that is, a shift from one psychological type to another; the third effect was a state of desolation; and fourth, he felt a sense of subtle bleeding.[1] Wolff interpreted the first effect as the reactivation of a suicidal tendency “that was in me [as] the result of something that had been done in past lives. It seems that, from what I have heard, that I have within myself—though the method is not known to this personality—the capacity to cut off life-force by the act of will.”[2] As for the second effect, Wolff states that “I had already learned enough of psychology to know that the wise thing to do was to cooperate” with it, which in his case, was a shift from a thinking orientation to a feeling orientation.[3] He notes that he was able to divert this shift into an interest in music (and particularly, in the operas of Wagner) and that he “was able later to control and reestablish the primacy of thinking.”[4] Wolff experienced the third effect—a sense of desolation—acutely on a few occasions, but felt that it “hung over me in a tenuous way—and was a problem I could not myself resolve.” He was most concerned with the fourth effect—that is, “a sense of subtle bleeding, not physical bleeding of the blood, but apparently the bleeding of the life-force itself”—for he was convinced that if he let it develop that it would inevitably lead to his death.[5]

Wolff found that he could not staunch this bleeding by any act of will, but that it did stop in the presence of certain women. Accordingly, he drew the conclusion that if he was to continue with his work that he would need to find a woman associate who had the power to stop the bleeding:

The stopping of the bleeding was not achieved by any conscious act of the feminine entities who affected the stoppage; [rather,] it seems to have been simply something that was in the constitution of the individual woman and that the process of stopping the bleeding was entirely unconscious and automatic. It resulted in my search for a companion who would go with me. And the conditions set: were that she would be available; that she was willing to go with me and preferably desired to go with me; and third, and most important, [that she] had the quality or whatever it was that would stop the bleeding.[6]

Wolff met several women who had the last ability, but who did not satisfy his other criteria—two were married and another had a religious orientation that he did not find compatible with his own. This led him to add another requirement: he wanted to find someone that was already associated with the work that he and Sherifa had started—that is, with the Assembly of Man. At the time there was an active chapter of this group in Chicago, and having had “no success in finding a companion . . . in the West, in due course a trip was made to Chicago in the search for a possible companion.”[7] There Eugene Sedwick, one of Wolff’s most steadfast students, introduced him to three women, all of whom had the power to stop the bleeding. Of these three, Gertrude Adams seemed to be the best candidate:

She had only a job as a commitment and that she could resign from. She was willing, and she had the full capacity to stop the bleeding. So I suggested to her that she should come out with me to California and spend a month living with me to determine whether it was a satisfactory relationship. She didn’t seem to think that she needed the month; but, in any case, I insisted upon it. So she resigned from her work . . . and came with Mary Miller and myself back to California.[8]

After the month ended, Gertrude “was not only willing, but seemed to be glad” to continue their relationship, and Wolff a “devised a symbolic service to constitute our real marriage” that was attended by nearby members of the Assembly; at this time he also gave her the name ‘Lakshmi Devi’, one of the four aspects of the Divine Mother as represented by Sri Aurobindo.[9] Early in September 1959 there followed a civil ceremony at the home of his stepson in Ajo, Arizona.

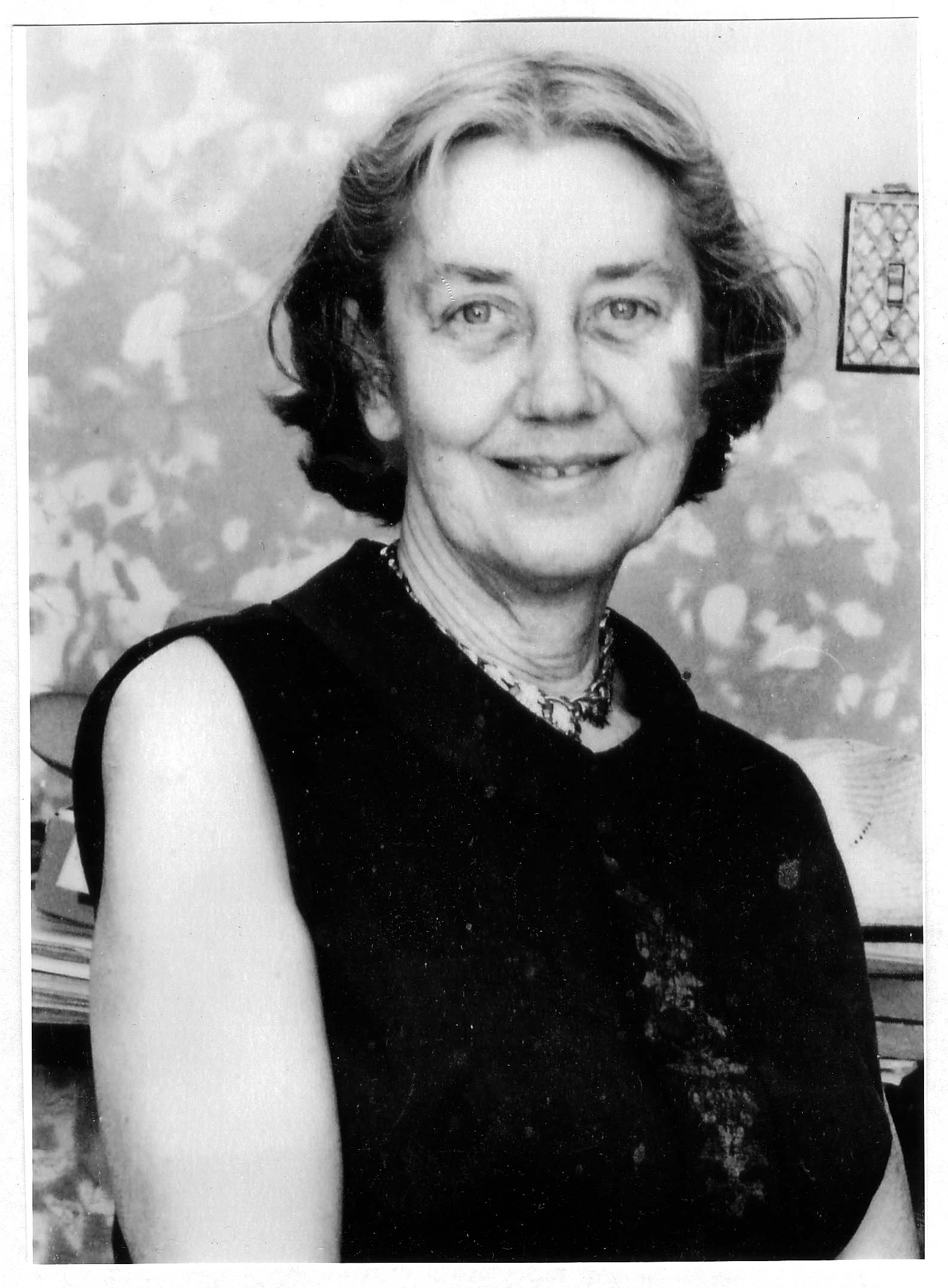

Gertrude Adams was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on May 30, 1911. Her father was a physician and claimed a relation to John Adams, the second President of the United States. Her mother (nee Maus) was of German heritage. Gertrude’s family moved to Lima, Ohio while she was a young child, where she and her two brothers were raised. Gertrude’s mother taught her how to play the piano, and after her mother’s death, Gertrude moved to Chicago where she found employment as a piano teacher. During World War II, she worked as a factory inspector; at the time of Wolff’s visit in 1959, Gertrude was working in the map department of the Chicago Park District.

Wolff relates that Gertrude became dissatisfied with orthodox Christian thinking and that on her own she developed the conception of reincarnation. Sometime later she was taking voice lessons from a woman who was a member of The Assembly of Man, and “was astonished . . . to find that here were people who took for granted thoughts which she imagined she alone had thought; and she was thrilled.” It was thus that Gertrude started her association with the group founded by Wolff and his first wife. Wolff goes one to state that “as I would analyze her psychologically, she was a thinking introvert; but I cannot say that intuition was strongly developed as the auxiliary function. And as a Gemini she, in a degree, tended to scatter her forces.”[10] In the late 1950s, Gertrude penned a book titled “Man Evolving,” which approaches the future of human evolution from a generally theosophical standpoint. The Wolff Archive contains two editions of this work, one from 1957 and another produced a year later.

Wolff’s marriage to Gertrude would have a profound effect on his life. Her presence immediately stopped the sense of bleeding felt by him, and her companionship also erased his sense of desolation as well as his desire for death.[11] This made it possible for Wolff to continue his work, which took several forms. First was the reactivation of the group work—that is, the Assembly of Man. In June 1960 Gertrude published the first issue of the Bulletin of the Assembly of Man, which had a run of thirty issues that ended in 1967. This periodical contained articles written by Wolff and other spiritual teachers, as well as notes composed by Gertrude and other members of the group.[12] In May 1967, the Bulletin was renamed “The Seeker” because the old name had “served its purpose.”[13] (Complete runs of both of these periodicals can be found on this website on the Organizations & Group Work tab of the Wolff Archive page under the section, “The Assembly of Man.”)

The couple also resurrected the annual Assembly of Man convention at the 430-acre ranch the organization had purchased outside of Lone Pine, California. They held their first convention in 1961 (one had not been held for over ten years) and this yearly tradition would continue until Wolff’s death in 1985. By this time the couple had permanently moved to the ranch from Santa Barbara, and they had begun planning to build a new home. Wolff reports that Gertrude had a serious interest in architecture, and that it was she who drew up the plans for house, which Wolff, Gertrude and one of Wolff’s students (Peter DeCono) finished building in 1963.[14]

At this time Wolff no longer composed at the typewriter, but instead recorded lectures on audiotape. He estimated that since his association with Gertrude he had “produced on tape perhaps half a million words,” and he remarks that this was

made possible because of what Gertrude had done—not knowing how she did it. Therefore, everything I have produced since then is the joint work of Gertrude and myself. Not because she contributed to the ideological portion of it, I did all that, but because she made it possible for me to produce. Her attitude toward me was one of single-pointed unbroken devotion.[15]

All of Wolff’s recordings—some two-hundred-forty essays covering topics that include philosophy, psychology, religion, politics, yoga, and more—can be found under the Audio Recordings tab on the Wolff Archive page of this website.

In July 1978, Wolff recounted his time with Gertrude as follows:

Gertrude was not simply a wife—that she was before the law—but she was a chela and my shakti, and that is a far closer relationship, who made possible the work we have done for the last nineteen years—a wonderful relationship, not one quarrel in nineteen years, not one cross word between us.[16]

Wolff recorded these words six weeks after Gertrude’s death from a stroke on what would have been her sixty-seventh birthday.[17] Her death hit Wolff hard, particularly so given that it was unexpected and that Gertrude was nearly twenty-four years younger than him. And her death resurrected some of the same symptoms that he had experienced after the death of his first wife, although “the bleeding did not recur and thus seem[ed] to have been cured.”[18]

Another effect of Gertrude’s death was the activation of a major archetypal dream that Wolff had had almost fifty years previously. With the help of Robert Johnson, a trained psychoanalyst, and Brugh Joy, a physician turned spiritual teacher, Wolff would spend much of the rest of his life working out the effects of the death of Gertrude and the activation of this dream. He explains:

It seemed that the “locked-in” condition between myself and Gertrude was preventing [the dream’s] activation, and it was suggested by [Robert Johnson] that she was withdrawn for the very purpose of precipitating that activation. The dream indicated that I had so far focused upon intellectual activity that it had drained the anima principle in my psychological constitution to the point where she was virtually exhausted. Whether this dream has, in fact, been activated—the evidence is in the strong enantiodromia—so that feeling is clearly a stronger force in my psychological constitution than it had been, and I found myself over the months that have followed until recently, virtually unable to tap the resources that had been my own previously. The process was a rather severe one. In fact, I seem to face the psychological effects due to the two events of the withdrawal of Gertrude, with its depression, and the activation of dream process.[19]

Robert Johnson advised Wolff that while his dream was very personal, it was also of collective importance. Wolff interpreted this to mean that he was personifying the problem of full Enlightenment, which in its completed form, concerns two aspects; namely, the principle of Wisdom and the principle of Compassion:

They are related to the chakras: one of the crown, which is sahasrara, and the other anahata, which is the heart center. The complete Enlightenment involves the activation of both, not of one alone. The Compassion is as fundamental a part of the functioning of the Sage or the Buddha as is the Wisdom; and there is evidence to believe that I personally am facing the activation of the anahata level, which nonetheless has proven to be an exceedingly painful process.[20]

Dr. Joy also emphasized the collective importance of Wolff’s struggles, not only in his grief over Gertrude’s death, but also with his preparations for his own death. Most of this material can be found in audio recordings that Wolff made after Gertrude’s death, and specifically, under the Autobiographical recordings found under the Audio Recordings tab of the Wolff Archive page on this website.

Endnotes

[1]Franklin Merrell-Wolff, “Self-Analysis of the Personal Problem” (Lone Pine, Calif.: November 15, 1978), audio recording.

[2]Franklin Merrell-Wolff, “Autobiographical Material: My Life with Gertrude (Part 1)” (Lone Pine, Calif.: October 31, 1978), audio recording.

[3]Ibid.

[4]Merrell-Wolff, “Self-Analysis of the Personal Problem.”

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Merrell-Wolff, “Autobiographical Material: My Life with Gertrude (Part 1).”

[8] Ibid. Wolff had previously met Gertrude, perhaps while on a lecture trip to Chicago, and also when Gertrude and a friend visited Wolff and Sherifa in Santa Barbara.

[9] Ibid. See also Franklin Merrell-Wolff, “Memorial Service for Gertrude” (Lone Pine, Calif.: June 4, 1978), audio recording.

[10] Merrell-Wolff, “Memorial Service for Gertrude.”

[11] Merrell-Wolff, “Autobiographical Material: My Life with Gertrude (Part 1).” Wolff notes that as for “the enantiodromia, I handled [it] myself.”

[12] A number of Gertrude’s articles have been transcribed and can be found in the attached listing of her work.

[13] The Seeker 1 (May 1967), 1. The Seeker had a short run (three issues) and Gertrude appealed to one of Wolff’s students (Bruce Raden) to continue its publication, but Bruce’s work and family obligations made this impossible.

[14] Merrell-Wolff, “Memorial Service for Gertrude.”

[15] Franklin Merrell-Wolff, “On the Place Gertrude Had in this Work” (Lone Pine, Calif.: July 11, 1978), audio recording.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Wolff believed that Gertrude “departed this realm on May 28, on or about noon, though [her death was] officially given the date of May 30, her birthday. Merrell-Wolff, “Memorial Service for Gertrude.”

[18] Merrell-Wolff, “Self-Analysis of the Personal Problem.”

[19] Ibid.

[20] Franklin Merrell-Wolff, “Impromptu Statement of My Present Condition” (Lone Pine, Calif.: August 1978), audio recording.