In 1928, I, along with eleven others, was appointed by an East Indian known as Yogi Hari Rama, [one of the] Disciples of the Absolute and we were assigned to the task of continuing a work which he had started [namely, Super Yoga Science], which consisted primarily in the teaching of certain techniques which he called keys . . . This was [an] adaptation of an Indian way of thinking to the American psyche.[1]

The Benares League of America was the largest yoga organization in the United Sates during the 1920s, and it was comprised of students of Yogi Hari Rama—whose story is fascinating. The “Yogi” had emigrated as Mohan Singh from the village of Himmalpura in the Punjub region of what is now northwestern India.[2] Singh first settled in Chicago, where he found employment as a domestic servant for several years, but he soon became enamored with a recent invention—the flying machine. Singh enrolled in the Glen Curtiss flying school in San Diego, and after two years he earned brevet #123 and became the first licensed pilot from India.

Singh also became a media sensation, and in a story that attracted national attention, it was reported that he was “a full-blooded East Indian captain in the British army in India,” who was “on furlough,” and that unbeknownst to his superiors, was studying aviation.[3] Sometimes he was given the rank of major; in one article he was described as an “Indian prince”; and, he was sometimes reported to be from Delhi or Bombay.

In point of fact, Singh was a first-rate aviator, and performed with the Curtis-Wright Aviators aerial circus, which billed him as “Major Mohan Singh (Licensed) of the Indian Army—Only Hindu Flyer in the World.” He later traveled to Hammondsport, New York to learn how to fly the Curtiss hydroplane. When the famous barnstormer Lincoln Beachey came out of retirement, he showed up at the Curtiss factory and was given permission to take up one of the “flying boats,” but was also advised to take Singh with him.[4] In 1913, Singh joined Glen Curtiss in marketing airplanes across Europe in the buildup to World War I. In 1916, Singh was reported as “on a list” of individuals that the War Department wanted as fliers for the United States.[5]

Singh found it difficult to sustain a career in aviation, however, and in 1914 he was working as a butler and chauffeur for a prominent family in Los Angeles. In 1919, he became a naturalized United States citizen, which at the time was only open to immigrants who were classified as Caucasian.[6] In 1922, Singh petitioned the court to change his name to Harry Mohan, given that his friends called him “Harry” and he did not want his last name confused with the common Chinese name ‘Sing’.[7] In 1923, the Federal government sought the cancellation of Singh’s citizenship, based on the grounds that at the time of his naturalization he was not qualified by race to be an American citizen. Early the next year, his appeal to have the motion dismissed was denied, and Singh was soon a man without a country.[8]

By 1925, Singh embraced his Indian (and more specifically, Punjabi) heritage and began his transformation to Yogi Hari Rama. He dressed in bright orange robes and lectured in various cities across California as “Dr. Hari Mohan” on topics about “Hindu philosophy” and “Yoga philosophy,” billing himself as a “Seer of India, Psychologist and Metaphysician.”[9] Late that year he introduced ‘Rama’ into his name, and by May 1926, Singh was lecturing in the Midwest as “Yogi Hari Rama,” making stops in Des Moines, Minneapolis, Detroit and Chicago.[10] He was by then teaching a system of yoga philosophy branded “Super Yoga Science” and which he promoted with the book,Yoga System of Study: Philosophy, Breathing, Foods and Exercises (H. Mohan, 1926).

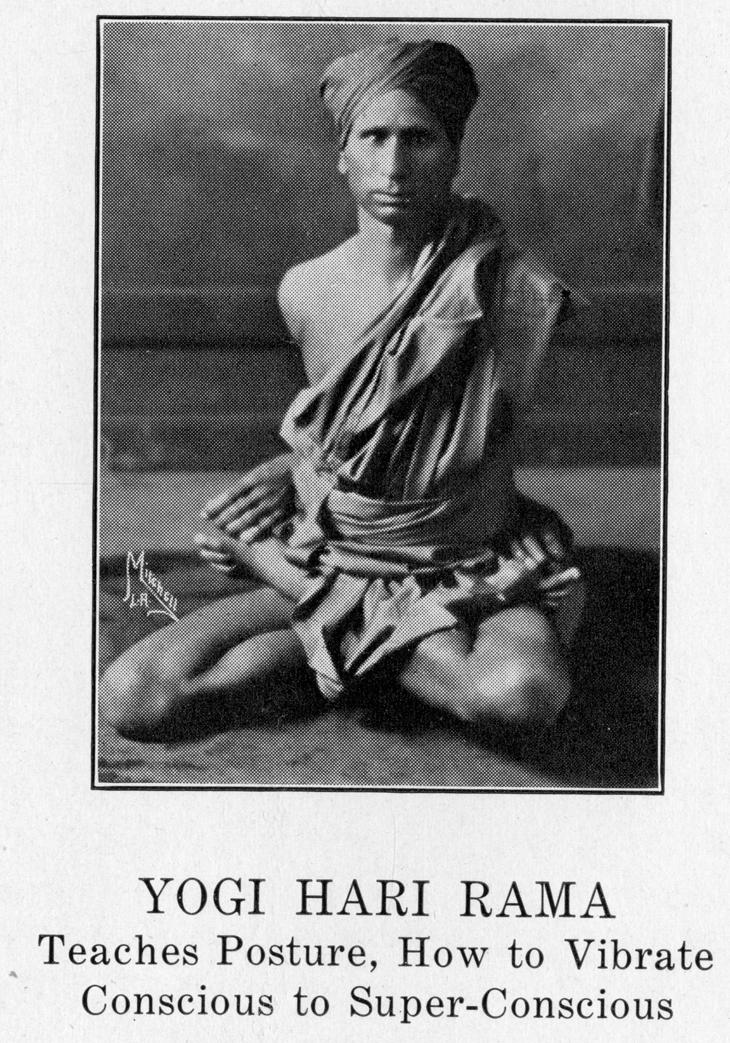

This volume, a copy of which is in the Wolff Archive, had a brief outline of his system of Super Yoga Science, including a diagram of the nadi system; some health advice that identified the two causes of human disease (psychological nerve symptoms and pyscho-physiological nerve symptoms); advice on marriage; a note that explains that there are three mental states or principles of consciousness: sub-consciousness, consciousness and super-consciousness (the latter said to be equivalent to “Christ-consciousness”); a note on the proper yoga breakfast; some breathing exercises, chants, rules on wearing colors and using decorations; some extracts from Rama Tirtha followed by uncredited poems and sayings; diagrams of a number exercises; about half of the book, however, consists of short cooking recipes. At the end of the book is the “illustration” of Yogi Hari Rama shown here. In 1927, this work was retitled Super Yoga Science and Yoga System of Study: Occult Chemistry combined with the Chemical Composition of Life Elements (H. Mohan, 1927). The Wolff Archive contains another book by “Yogi Hari Rama of India, Psychologist and Metaphysician,” titled Human Life and Destiny (H. Mohan, 1927), which contains additional anatomical drawings and metaphysical information from the system of Super Yoga Science.

causes of human disease (psychological nerve symptoms and pyscho-physiological nerve symptoms); advice on marriage; a note that explains that there are three mental states or principles of consciousness: sub-consciousness, consciousness and super-consciousness (the latter said to be equivalent to “Christ-consciousness”); a note on the proper yoga breakfast; some breathing exercises, chants, rules on wearing colors and using decorations; some extracts from Rama Tirtha followed by uncredited poems and sayings; diagrams of a number exercises; about half of the book, however, consists of short cooking recipes. At the end of the book is the “illustration” of Yogi Hari Rama shown here. In 1927, this work was retitled Super Yoga Science and Yoga System of Study: Occult Chemistry combined with the Chemical Composition of Life Elements (H. Mohan, 1927). The Wolff Archive contains another book by “Yogi Hari Rama of India, Psychologist and Metaphysician,” titled Human Life and Destiny (H. Mohan, 1927), which contains additional anatomical drawings and metaphysical information from the system of Super Yoga Science.

In 1927, Yogi Hari Rama lectured in Chicago, St. Louis, Indianapolis, Rochester, N.Y., and New York City; advertisements can be found for 1928 lectures in newspapers published in Brooklyn, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, and Los Angeles. He would often stay in a city for weeks at a time, lecturing on Super Yoga Science and other topics, and his publicity touted that he was “the first teacher from the Orient to bring the Western World concrete knowledge of a scientific method of applying mind to matter”; in addition to his lectures on “Hindu Philosophy” he taught “nine secret keys . . . passed from master to pupil since time began.”[11]

There were a number of other Punjabi yoga teachers in the United States about this time, and two acknowledged knowing Hari Rama: Yogi Wassan referred to him as his “Guru Brother” in a 1941 display advertisement and Rishi Singh Gherwal referred to “many years of friendship” between himself and Yogi Hari Rama in a 1930 pamphlet. In an article that focuses on the Punjabi Sikh presence in early American yoga, Phillip Deslippe notes it is likely that these individuals were familiar with one another and that once they each began to teach yoga, that they comprised a well-connected network:

If they could be thought of as merchants, they could also be thought of as a type of guild that exchanged information and offered mutual assistance. There have been several studies that have explored the effects social networks have among immigrant communities into bringing members into a shared occupation and fostering success within it, and the Punjabi Sikh presence in early American yoga can be seen as an example of this. While still viewing them as distinct individuals, their tightly-knit circle and similarities (along with their emergence as teachers mostly over a short period of a few years in the 1920s) are strong reasons for also thinking of . . . Punjabi Sikh yoga teachers as a single cluster.[12]

It would seem likely, then, that the transformation of Mohan Singh from pilot to yoga teacher was the result of his membership in a craft guild and that he was not—as his students often touted—a yoga master who had come to America specifically to teach the wisdom handed down by the holy men of India.

It should be noted that this period was just after World War I, which was a time when many in America were reassessing their values and searching for a “higher knowledge.” For instance, a disciple of Hari Rama proclaimed that the “monstrosity of the recent war” has revealed “that we stand at a critical point in the history of our culture” and that the “fruit of Yoga” is needed “because our present culture has failed to meet our deepest needs.”[13] It was, quite obviously, a lucrative period in America for the peddling of metaphysical thought. Moreover, given that increasingly restrictive immigration laws made Indian emigrants few and far between, the “sages” of this Punjabi guild represented a source of knowledge that was a rare commodity. Deslippe explains the situation as follows:

[At the time], the pull towards India was most acute within America’s metaphysical seekers. The ground laid by Transcendentalists, Theosophists, and New Thought in the nineteenth century helped to establish . . . an imagined East that held timeless and powerful spiritual truths in the minds of American seekers. Having little contact with Indian immigrants but endless exposure to fantastic tales of magical fakirs and supernatural yogis through written accounts and stage magicians, the default assumption of most Americans was that the average Indian was capable of working wonders . . .[14]

In the case of Yogi Hari Rama, a 1927 newspaper article reported that he was “proclaimed by more than 700 followers as a miracle man, among whom it is claimed he is able to walk on water in an emergency.”[15] It was in fact often enough to simply advertise oneself as an Indian master of Hindu Philosophy, or as “Dr. Hari Mohan” first did, as an “Indian seer,” to attract large gatherings.

Singh made a small fortune as Yogi Hari Rama, and at the end of his tour in late summer 1928, he vanished without a trace.[16] His departure from public life was evidently planned, as an advertisement in that year’s August 27 issue of The Los Angeles Times states that “Tonight [is] absolutely your last chance to hear the Hindu Master Yogi Hari Rama.”[17] A September 14, 1928 letter to “Local Chapters of Benares League” explains that “at the end of Yogi Hari Rama’s class work in this country and before leaving us, he entered Samadhi and then appointed twelve disciples . . . to carry on the Master’s work in this country.”[18] One of the disciples on this list is “Dr. Franklin F. Wolff” of San Fernando, California, who it is noted, will “start shortly” at the Chicago chapter of the League.

Although the letterhead for the stationary of the Benares League of America states that it was founded by Yogi Hari Rama, there is no mention of the organization in the advertisements for his lectures. A. William Goetz, another of Hari Rama’s twelve official disciples, is quoted in a 1933 newspaper article as stating that “Yogi Hari Rama came to America seven years ago and spent 3½ years teaching this [Super Yoga Science] here. He had more than 10,000 pupils in that time and they have banded together to form the Benares League.”[19] This would lead one to think that the Benares League was formed in anticipation of Hari Rama’s departure; it is also clear that local chapters were franchises with fifty-percent of their revenue payable to the national headquarters.[20] The Benares League was still was meeting in 1938, when it held a quarterly convention at the Henry Hotel in Pittsburgh; the program included a talk by Stanley Reland, also one of Hari Rama’s original twelve disciples.[21]

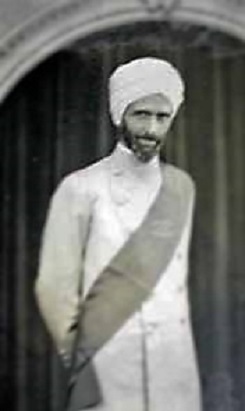

Wolff does not explicitly state when he and his wife first made contact with Hari Rama or the Benares League of America. Since Yogi Hari Rama frequently lectured in the Los Angeles area, the couple could have heard him speak as early as 1925. As indicated by the letter above, Wolff became formally involved in 1928, and his work began in earnest in early 1929. Following in Mohan Singh’s footsteps, Wolff took on the suggestive pseudonym, “Yogagñani,” of whom there are several pictures in the Wolff Archive, including one of him garbed in a white robe with a sash labeled “Disciple of the Absolute” and wearing a turban. These trappings were clearly meant to parlay a connection between the Benares League and the mysteries of the Orient, and the turban was an especially strong artifact of the League’s connection to the Punjabi teacher’s guild. Indeed, Deslippe explains (quoting Herman Scheffauer) that for the Punjabi teachers of yoga in America the turban was a “badge and symbol of their native land”; Deslippe then notes that “the salience and visibility of the turban also made it a marker for the other side of America’s Orientalist imagining of Indians as mystical sages and mental wonder-workers.”[22]

Wolff does not explicitly state when he and his wife first made contact with Hari Rama or the Benares League of America. Since Yogi Hari Rama frequently lectured in the Los Angeles area, the couple could have heard him speak as early as 1925. As indicated by the letter above, Wolff became formally involved in 1928, and his work began in earnest in early 1929. Following in Mohan Singh’s footsteps, Wolff took on the suggestive pseudonym, “Yogagñani,” of whom there are several pictures in the Wolff Archive, including one of him garbed in a white robe with a sash labeled “Disciple of the Absolute” and wearing a turban. These trappings were clearly meant to parlay a connection between the Benares League and the mysteries of the Orient, and the turban was an especially strong artifact of the League’s connection to the Punjabi teacher’s guild. Indeed, Deslippe explains (quoting Herman Scheffauer) that for the Punjabi teachers of yoga in America the turban was a “badge and symbol of their native land”; Deslippe then notes that “the salience and visibility of the turban also made it a marker for the other side of America’s Orientalist imagining of Indians as mystical sages and mental wonder-workers.”[22]

As head of the Benares League’s Chicago chapter, Wolff’s work was centered in the Midwest as well as near his home in the Los Angeles area. A March 2, 1929 announcement for “Free Lectures [by] Yogagnani” in Indianapolis notes that he is a “Grad of Stanford and Harvard Universities” and that “Classes in Mantra Yoga are forming.”[23] Another advertisement for lectures by Mr. Franklin Merrell-Wolff states that “He is the only American who has won the powers of his Sanscript [sic] name—Yogagnani,” and that “Thousands have applauded this great Thinker and Speaker. His students have power and understanding. They say he has taught them how to change failure into success and how to be dominant centers of power.”[24]

At the very least, it is clear that Wolff had learned the art of self-promotion from Hari Rama. There is anecdotal evidence, however, that Wolff did not care to dress up in the “costume” pictured here, which was apparently his wife’s idea.[25] More importantly, Wolff found something unsettling about Hari Rama’s commercialization of yoga; in particular, he explains that he was uneasy about the Benares League’s monetization of the information found in yoga:

When in 1928 I played a part as an appointed Disciple of the Absolute to continue the work initiated by one called Yogi Hari Rama, there was a policy prescribed by him on the economic side. Those who came to receive the instruction in the use of certain devices called “keys” that were supposed to serve in producing health and certain other effects, the policy was laid down by Yogi Hari Rama himself: it was a formal charge for these. I continued this policy because it was prescribed by him, but never felt comfortable about it. When we ceased to be associated with that work, I reverted to the basis of free contribution.[26]

The crux of the matter here lies in the approach that these two took to their work. For Yogi Hari Rama, the teaching of yoga was a learned craft and as such, a means of living. Wolff, on the other hand, was in sympathy with the policy of the United Lodge of Theosophists, according to which one’s means of living was to be separated from one’s public or “spiritual” work, and that no income should be derived from the latter.[27] The practical result was that although Wolff and his family never knew “privation or an economic deficiency that cost any hardship . . . we never have been flush.”[28] Mohan Singh, on the other hand, was apparently able to retire as a wealthy man.

As Wolff would learn, there was an important reason for not treating yogic knowledge simply as a commodity. He explains:

In 1928, I, along with eleven others, was appointed by an East Indian known as Yogi Hari Rama, “Disciples of the Absolute,” and we were assigned to the task of continuing a work which he had started which consisted primarily in the teaching of certain techniques which he called “keys.” . . . In general, a warning was given not to use these to any great extent, but only with great restraint. I have given these keys in my experience in the past and have given this warning, but one of the students ignored the warning completely, used excessively one of the keys, and called down upon himself a fire which he was totally unable to control. In the end, he had to be entered into a psychiatric institution. This awakened in me a realization that this was dangerous stuff and that a mere verbal warning is no adequate protection of the sadhaka at all. He must be first trained in the seriousness of violating instructions, and that does not exist naturally in our rather superficial and casual Western consciousness in these matters.[29]

Wolff’s point seems to be that there is a responsibility carried by the transmission of this knowledge, and this component makes it more than a simple economic transaction. Accordingly, Wolff sought to correct some of these deficiencies on his own. For example, his class notes during this period include a number of statements on the “No Charging Principle,” such as “Spiritual service which includes the teaching of metaphysics can never be evaluated in terms of material coin and is at once lowered when a price is placed upon it” and “It is not right that any earnest student should be denied such spiritual service because of his economic condition.”[30]

Wolff also complained that the teachings of the Benares League underestimated the abilities of the “Western” thinker:

[For example, there] was a certain identification or adjustment to Western thinking in one of the principle keys which ran this way: twenty parts of the body, attention with the will, low/medium/high—vibrate. It was explained that this low, medium, high was an adaptation to our practice in driving automobiles. First, you put the lever into low, then into intermediate, and finally into high. This was adaptation of an Indian way of thinking to the American psyche. But, I think we in the West are more sophisticated than that in our depth psychology and in our metaphysical philosophy, and I have always felt that this was something of an undervaluation of our intelligence.[31]

Wolff sought to remedy this situation by augmenting his lectures and classwork with material not taught by Yogi Hari Rama. Indeed, his notes reveal that his coursework during this period evolved from classes as advertised—that is, on “Mantra Yoga”—to “Mantra-Jnana Yoga Classes.”[32] The former followed Hari Rama’s emphasis on the “keys” as well as diet, breathing and exercises;[33] the latter begin to introduce the “importance of being well-grounded in philosophy.” Wolff’s Benares League lectures, outlines of which can be found in the Wolff Archive under the Lectures, Notes & Outlines tab, also make use of material that Wolff gleaned from Theosophical, scientific and literary sources.

Wolff’s most explicit ideological statement at this time was in the form of three books.[34] The first two were self-published by The Merrell-Wolff Publishing Co. in 1930 and penned by Yogagñani: Yoga: Its Problems, Its Purpose, Its Technique is advertised with the note that “this volume brings to the reader a statement of the problem of Life which Yoga solves, the principles upon which that solution is based, and a concise statement of the seven principle technical forms by which those principles are applied practically”; the Introduction to Re-Embodiment, or Human Incarnations states that it “is designed to serve two purposes. In the first place, the rational ground for belief in the reality of reincarnation together with evidences supporting the validity of the teaching will be elaborated. After that there will be a discussion of what might be called the technique of Reincarnation.” The third book written by Wolff around this time was titled “Death and After”; it was never published and the Wolff Archive contains several drafts. In this work, Wolff first introduces the “problem of death” and then considers the philosophical meaning of death, life and consciousness, birth and death in relation to life, and the constitution of man according to the arcane schools. The next four chapters respectively address the planes of consciousness and Being; the constitution of man in relation to the planes of consciousness, Kama Loka; and Devachan. In the final chapter Wolff discusses mediumship and spiritualism.

“Death and After” draws on much of the material found in Wolff’s lecture outlines, and references diverse sources such as Count Hermann Keyserling, various forms of Buddhism, J. J. Jeans and other scientific authorities, Western philosophy, Ramakrishna, Vivekananda, and especially the theosophical thought found in the Secret Doctrine of H. P. Blavatsky and in the Arcane School. The first two books offer “an outline of the rationale of Yoga as a basic philosophy and as a science of life practice” by “casting into a western rational form the metaphysical material which comes out of the East—that is, by blending the oriental focus on Being with the occidental focus on Form in order to adapt an Indian way of thinking to the American mind.[35] Wolff describes Yoga as “a science based on a philosophy . . . that man is in reality God”[36] and that as such it “is a technique by which new cognitive powers may be awakened . . . [It] is the life practice designed to produce a favorable condition for the Realization . . . of that which is formulated in [the] philosophy of Wisdom Religion”—that is, “the destruction of the false ego and the Realization of the One Self.”[37]

By December 1930, other disciples in the Benares League have learned that Wolff’s work has gone beyond the teachings associated with Hari Rama. In the December 1930 issue of The Disciple, a newsletter published by the League, it is noted that “Mr. Franklin Wolff is now teaching work of another nature not connected with Super Yoga Science Teachings by Yogi Hari Rama.” In the same issue, the editor states that

The Eastern Lodges of the Benares League are requiring a written statement from Disciples that they and their staff are not actively engaged in teaching any other work than that taught by Yogi Hari Rama. That they are not connected with any Inner Circle Teachings while teaching as a Disciple . . . They have taken the stand that a House Divided Against Itself Cannot Stand and that all Disciples should be whole hearted for the nine keys and place their entire efforts in that direction.[38]

At this time, Wolff also received three letters (dated December 15, 1930) from some attendees of a Super Yoga Science class in Des Moines.[39] Each writer relays what they perceived as a disturbing occurrence at the class, which in the letter of Charles Wilson is as follows:

The last night of the open lecture I am there with my wife and quite a number of students. The assistant of the lecture is out in the hall and is making remarks about you being a crook and passing Government bonds and doing time. I spoke to him and invited him to come see me at the Temple the next morning, which he did. I told him this is a malicious story and you should take it to a lawyer.

Mr. Wilson goes on to speculate whether the rumors started within the Benares League.

Wolff and his wife do not appear to have responded to these letters or to the charges in the December 1930 newsletter; the latter, of course, are quite true. In fact, before Wolff had even begun his work for the Benares League, he and his wife had formed their own religious association—a group that they would eventually come to call “The Assembly of Man.”

Endnotes

[1] Franklin Merrell-Wolff, “Yoga of Knowledge” part 2 (Lone Pine, Calif.: September 12, 1970), audio recording, 7.

[2] Most of the following is based on the work of Phillip Deslippe. See his “In 1912, Mohan Singh Was Billed as ‘The Only Hindu Flyer in the World’ in Air & Space Smithsonian Magazine at airspacemag.com (February 7, 2017) and “Rishis and Rebels: The Punjabi Sikh Presence in Early American Yoga” Journal of Sikh & Punjab Studies, 23:1-2 (2016), 93-129.

[3] As reported in the The Day Book (Chicago, Ill.: April 16, 1912), 20.

[4] As reported in the Elmira, N.Y. Star-Gazette (September 29, 1913), 12.

[5] New York Herald (October 6, 1916), 1; this report states that “Lieut. Mohan M. Singh is a Chinese army officer.”

[6] The Los Angeles Times notes that the court held that “Singh is a high-caste Hindu, competent in moral and intellectual respects to be a citizen of the United States” (March 25, 1919), 9.

[7] The Los Angeles Times (March 18, 1922), 24.

[8] The Los Angeles Times (February 12, 1924), 25.

[9] See, for example, the advertisement (with a photograph of Singh) in the Santa Ana Register (April 17, 1925), 12.

[10] An incident in late August 1925 may have been what precipitated the name change; specifically, the former principal of a Los Angeles high school was arrested in Singh’s Oakland apartment. Thomas Russell had been arrested earlier in the year for contributing to the delinquency of a minor boy, but found guilty of vagrancy. He jumped bail before the start of his six-month prison term, and at the time of his arrest in Oakland, he told police that he was Dr. Mohan’s manager. The police reported that when they entered the apartment “they found Dr. Mohan garbed in a red turban and long red robe.” The Los Angeles Times reported that Mohan was a “Hindoo palmist and metaphysician”; the Oakland Tribune story noted that he was a psychologist. A lecture by “Master of Yoga Philosophy, Dr. Hari Mohan . . . India” was scheduled for the next day (as advertised on p. 14 of the Oakland Tribune (August 29, 1925); the name on the next month’s lecture advertised in the paper was changed to “Sri Dr. Hari Rama Mohan, Hindu Master Guru and Yogi of Benares, India” (September 12, 1925, 16).

[11] Suburbanite Economist (Chicago, Ill.: December 3, 1928), 5. The keys, in their “public” form, were: Key 1: Self-mastery, which includes self-control and self-healing; Key 2: Control life energy, or Prana (breath), and two optic nerves; Key 3: Unfold God-consciousness, Christ-consciousness or Super- consciousness; Key 4: Healing other people from the state of Super-consciousness by (1) visualization, (2) concentration, and (3) meditation; Key 5: Learn about the law of compensation and natural balance; Key 6: Awaken the Kundalini, or creative principle; Key 7: Awakening the solar power or the "higher occult forces;" Key 8: Unfold the seven spiritual gifts of wisdom, bliss, light, glory, power, honor and strength; and Key 9: Awaken the unlimited, spiritual Power.

[12] Philip Deslippe, “Rishis and Rebels,” 116. Deslippe also notes that among this group, Rishi Gherwal “was the most interested in yoga qua yoga both in the modern postural forms that are recognized today and in its classical textual forms. His published works were filled with references to older texts such as the Yoga Vasistha, Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra, the Prashna Upanishad, the Kundalini Upanishad, and the Hatha Yoga Pradipika” (ibid., 101-2).

[13] This disciple was none other than Wolff himself (writing under the pseudonym of “Yogagñani”) in “Civilisation: Looking Forward” (Wolff Archive: Lecture Notes, 1929), 1; see also, Yogagñani, “Yoga and its Transforming Power,” (Wolff Archive: Lecture Notes, 1929), 2.

[14] Deslippe, “Rishis and Rebels,” 109.

[15] Star-Gazette (Elmira, N.Y.: February 1, 1927), 17. Of course, it was not always the case that the media was so enamored; for example, a 1927 story was national distributed with the headline “Fakir who claims to walk on water ropes in gullibles” Shamokin News-Dispatch (Shamokin, Penn.: February 4, 1927), 2.

[16] Deslippe, “Rishis and Rebels,” 109.

[17] Los Angeles Times (August 27, 1928), 4.

[18] “Letter from Benares League of America National Headquarters to Local Chapters,” September 14, 1926.

[19] The Madison Eagle (Madison, N.J.: November 24, 1933), 6.

[20] Ibid.

[21] The Pitsburgh Post-Gazette (July 13, 1938), 6. Charles Schoelen (Yogi Shalom), Director of Yoga of the Old Masters, states on his website that “I have been told that I am the only surviving student of the Benares League of America. Here I studied Super Yoga Science. Super Yoga Science is the study of the Science of Eastern Yoga. As a student to the school, the prerequisite was to be proficient in Hatha Yoga. I studied there for three years learning mental control of body, mind and emotions. I was able to incorporate many advanced teachings into our current meditations.” Accessed May 3, 2017. http://www.yogaoftheoldmasters.com/about.html.

[22] Philip Deslippe, “Rishis and Rebels,” 110.

[23] The Indianapolis News (March 2, 1929), 11.

[24] The Indianapolis News (March 16, 1929), 8.

[25] See, for example, his step-granddaughter’s recollection in Doroethy B. Leonard, Franklin Merrell-Wolff:An American Philosopher and Mystic: A Personal Memoir. (Self-Published, Exlibris, 2017), 96.

[26] See Franklin Merrell-Wolff, “Autobiographical Material: A Recollection of My Early Life and Influences” (Lone Pine, Calif.: July 6, 1978), audio recording, 4.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Merrell-Wolff, “The Yoga of Knowledge,” part 2, 7.

[30] Yogagñani, “Notes for Mantra-Jnana Yoga Classes” (Wolff Archive: Organizations & Group Work, no date), 41.

[31] Merrell-Wolff, “The Yoga of Knowledge,” part 2, 6.

[32] Merrell-Wolff, “Notes for Mantra-Jnana Yoga Classes.”

[33] These class notes also outline some Mesmerist and New Thought techniques for healing others or realizing material wishes, which may have been part of the Benares League curriculum.

[34] Yogagñani, Yoga: Its Problems, Its Purpose, Its Technique (San Fernando: Merrell-Wlff Publishing Company, 1930); Yogagñani, Re-Embodiment or Human Incarnations (San Fernando: Merrell-Wolff Publishing Company, 1930); and, Yogagñani, “Death and After,” (n.p.: ca. 1930). Several other books are listed as “in preparation” in the back matter of Yoga and as “authored by” in Re-Embodiment; these titles include “Adepts and Avatars,” “Astral Light Explained,” “Conditional Immortality,” “Occult Powers Resident In Sound,” and, “Western Science and the Ancient Wisdom.” Although there are lecture notes in the Wolff Archive with these titles, no manuscripts have been found.

[35] Yogagñani, Yoga, 7; Yogagñani, Re-Embodiment, 10. “The cultures of the East and the West have developed in diametrically opposed directions,” whereby India reflects subjective mystical genius and Europe objective material genius. Each comes across as inferior to the other, but “[i]f the metaphysical significance of the now superficially familiar Theory of Relativity were more generally understood, this mistake would not be made. No one culture can possibly afford an absolute criterion.” Yogagnani, Yoga, 9; Yogagnani, Re-Embodiment, 9.

[36] Yogagñani, Yoga, 25. Similar ideas are also found throughout his lecture notes; as an example, see Yogagñani, “Civilisation: Looking Forward,” (Wolff Archive: Lecture, Notes & Outlines, 1929), 1.

[37] Yogagñani, “America in Relation to the World-Crisis,” (Wolff Archive: Lecture, Notes & Outlines, ca. 1933), 1-2; Yogagñani, “Yoga and its Transforming Power,” (Wolff Archive: Lecture, Notes & Outlines, 1929), 1. Here is how Dave Vliengenthart summarizes Yogagñani’s system of yoga:

If this metaphysics sounds more like a psychology than a philosophy, that is no surprise, since Yogagnani presumes that Yoga “places primary reality in Consciousness.” Regardless whether or not there is a reality as such, the only meaningful reality that exists for us is the one that is wholly dependent on consciousness. Since individual consciousness is identical with pure consciousness, “in psychology, in [the] sense of self-analysis, is found [the] key to all knowledge.” This line of reasoning implies that every problem is actually a cognitive problem, which leads him to surmise that “Yoga Philosophy has the critical spirit, in the Kantian sense, and builds metaphysics upon epistemology.”

His Yoga, then, focuses on jnana or Knowledge—with a capital k, given that it is “both intellectual and Spiritual . . . what might be called intellectio-spiritual knowledge.” In western terms, he is talking about gnosis. There are many different routes of Yoga—seven, by Yogagnani’s count—but only the Path of Knowledge or Jnana Yoga can lead to liberation, he thinks, since there is nothing to do and nowhere to go, except to know that “you are (already) that”—tat tvam asi. Needless to say, this is an “advaitized” Yoga—reminiscent of Roy and Vivekananda—which centers on the realization or immediate religious experience of moksha, as a non-dualist state of consciousness that needs yet exceeds the intellect.

Dave Vliegenthart, The Secular Religion of Franklin Merrell-Wolff: An Intellectual History of Contemporary Anti-Intellectualism In America (Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2018), 107-8.

[38] The Disciple (December 1, 1930).

[39] These letters are from Charles Wilson, Thomas Hill, and an unknown third correspondent.